Transcription Conventions

In the transcriptions for the Pulter Project, we preserve as many details of the original material, textual, and graphic properties of Hester Pulter’s manuscript verse as we have found practical. Below we enumerate many of those details, not least so that our working procedures may be understood and checked for consistency. We appreciate corrections from readers, which we will strive to integrate in a timely way. Exceptions to these rules are detailed in notes to individual poems.

-

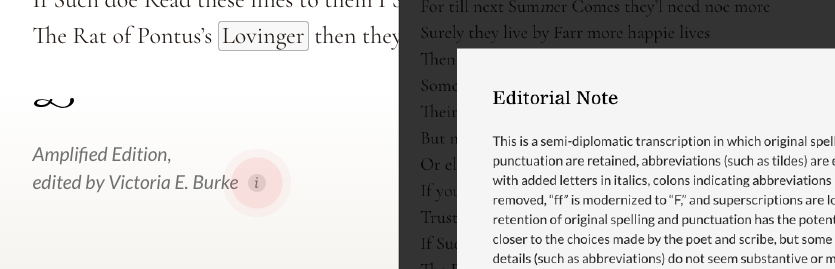

Whenever practical and possible, original spelling, punctuation, capitalization, lineation, spacing between words and lines, and indentation are maintained. Abbreviations and brevigraphs are not expanded; superscript and subscript representations are retained; and medieval thorns, which resemble modern “y”s, are transcribed as such. Titles are, however, justified to the left margin.

-

While we attempt to record every letter, we do not consider the superscript mark resembling “e” (a mark the main scribe used frequently) to be a separate letter; it appears to be a variation on the kind of flourish sometimes appended to minuscule “e” in secretary hand. Since we consider this mark part of the preceding letter and since readers might misidentify this graphic mark as a separate letter, we do not record it separately.

At times, it has proven impossible to discern a difference between certain letter forms, such as “I” and “J” or “u” and “v.” In these cases, we select the letter form that best corresponds with modern spelling and pronunciation (not “Iury” but “Jury,” for instance).

Similarly, at times it is difficult to discern the difference between majuscule “S,” minuscule “s,” and the elongated version of the same letter: “ſ.” In other manuscripts using “ſ,” it often has a descender (below the line); we feel it is often used here without that descender, and is thus easily confused with majuscule “S.” We have, with an eye to modern usage, reserved majuscule “S” for the start of words, rather than the middle or end.

Likewise, the main scribe appears to use two forms of majuscule “R”; and a shorter version of one of these also appears at times as a minuscule. In such cases, we have made decisions based on the relative ascension of the letter to determine if it is majuscule or minuscule.

-

Page numbers from the manuscript that are contemporary with the initial inscription (those in ink) are retained, though we have located these uniformly on the left; the same is true of emblem numbers, which we have uniformly placed on the left in the line before the first line of the poem. We do not transcribe the numbers in pencil added by librarians at Leeds. Foliation is centered, in square brackets to indicate that this is our addition. Catchwords, which are frequently but not consistently used by the main scribe, are retained. Although we do not attempt to represent accurately the amount of space between the top of a sheet or a title and the start of the text, we note when a poem does not begin at the top of a page, or when there is unusual blank space separating poems.

-

Cancelled words are struck-through. If the manner of cancellation is anything other than a single horizontal line (e.g., if it is a double or triple line, a vertical or diagonal line, scribbled, erased, or blotted), that manner is addressed in a note. When cancelled words or letters are still fully or partially legible, the legible words and letters are either included in the main text and struck-through or, if necessary (especially when written over by other legible letters), described in a note. When cancelled letters are illegible, a single struck-through question mark appears in the main text, with an explanation in a note if necessary.

-

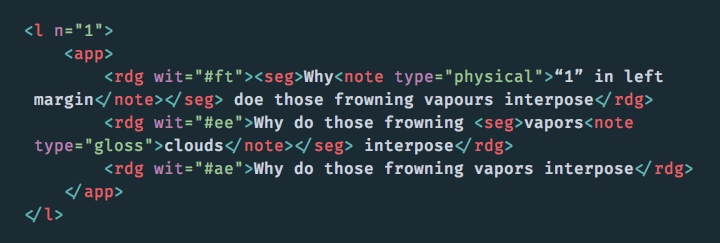

When the transcriber is unable to decide between multiple readings, the various possibilities are noted.

-

Interlinear insertions are represented in superscript or subscript, as in the manuscript; they are marked by a caret (^) or any other insertion symbol present. In many cases, for instance, a back slash (\) appears below the line where a superscript insertion occurs, and another appears above the line immediately after the insertion. At times, a superscript insertion appears directly above other words, rather than between or beside them; these cases are noted.

-

Lines at the ends of poems are described in square brackets.

-

Changes in hand and ink are noted where they are obvious or likely.

-

Marginalia is transcribed in a note, with the note’s superscript numeral placed at the end of a word as close as possible to the original location of the marginal item.

-

When the same title is used for more than one poem (as with “Aurora,” e.g.), poems are distinguished by a numeral in square brackets: e.g., “Aurora [1],” “Aurora [2],” and so on.

-

Other than superscript numerals keyed to footnotes, and forward slashes used to indicate line breaks, material not in the original manuscript is enclosed in square brackets or described in footnotes.

-

We note when the hand changes from that of the main scribe (H1); we consider H2 to be probably that of Hester Pulter, and H3 to be an eighteenth-century hand.